Yesterday saw @analyst941 delete his Twitter account, claiming that he had been forced to do so after Apple carried out a “multi-step sting” operation. Whether this is true, or just a face-saving story for getting things wrong, it is broadly consistent with what we know about how Apple catches leakers.

Apple has so many methods of identifying leakers – some of them incredibly subtle – that we and others have to be extremely careful in order to protect our sources …

Apple’s secrecy culture

With most tech companies, secrecy is a way to stop competitors beating them to the punch. If they know or suspect other companies are working on the same idea, they want to be first to market, so don’t want anyone else to find out their plans, or how close they are to launching.

With Apple, however, the company’s primary motivation is different. The company rarely aims to be first to market; instead, it watches and waits while other companies rush products out of the door, and figures out how to improve on their offerings. Apple aims to be best, not first.

But it does still want to protect its future plans, and that’s due to a realisation Steve Jobs had: that there is magic to a sudden reveal. The launch of the original iPhone is the most famous example.

Today we’re introducing three revolutionary products of this class. The first one is a widescreen iPod with touch controls. The second is a revolutionary mobile phone. And the third is a breakthrough Internet communications device.

The reveal, of course, was that they were all the same device.

It is this desire for the magic of surprise which forms the main driver for Apple’s culture of secrecy.

How Apple protects its secrets

The Cupertino company has many ways of protecting its secrets.

For example, it has a silo system for product development. Individuals, or small teams, will be working in isolation on one element of a product, while other teams – whose existence isn’t even known to each other – will be working on other elements. Product developers aren’t allowed to share their work, even with other Apple employees (one of the reasons that the famous Apple Park circular design to encourage collaboration is more PR image than reality).

In some cases, employees don’t even know what product category they are working on. For example, they may be working on audio tech without even knowing whether it will be used in a HomePod, a Mac, AirPods, or iPhone speakers.

Prototype devices are very carefully disguised if they need to be used in public, with great care taken to log and track them – a lesson Apple learned the hard way, after the infamous iPhone 4 prototype bar incident!

IT systems will of course be carefully protected, Apple monitoring both network activity and use of things like USB keys.

Apple also warns employees that leaking information is a fireable offence – and that the company may even go after them for financial damages.

All the same, some employees do leak information, and even with a silo system, there will be some Apple secrets known to a significant number of people. When information is leaked, the company needs some way to identify who leaked it, and it has some pretty sneaky ways to do so! These are just a few answers to the question of how Apple catches leakers …

How Apple catches leakers

Given Apple’s emphasis on product design, it’s no surprise that the company works particularly hard to prevent leaks of visual materials: product images, drawings, blueprints, CAD images, and the like.

It used to be commonplace for tech sites to share these images directly, but Apple came up with a wide variety of ways to identify exactly which copy of an image was shared. Each individual who received an image would be given a unique one.

Here are just a few of the methods Apple is known or believed to use …

Invisible watermarks

We’re all familiar with visible watermarks used by sites such as ourselves, to ensure that original images are properly credited, but it’s also possible to embed watermarks which are invisible to the naked eye, but can be digitally detected.

For example, this square appears to be all black:

In fact, one section of it is #0D0D0D instead of #000000. By making changes as subtle as this to different pixels, you can create a near-infinite number of variations, each of which would be impossible to distinguish by eye.

We’ve used black as an example, but the same can of course be done with literally any color in an image.

This is the reason why we never share actual images supplied by our sources. We always recreate them, and never exactly.

Filenames

Another reason never to use original images is that it’s very easy for Apple to use unique filenames, for example:

- very_secret_image_46793459583203.jpg

- very_secret_image_46793469583203.jpg

Serial numbers

Document serial numbers is another variation. For example, when Apple shares videos with employees, each is watermarked with an ID number which is likely cross-referenced with the Apple Connect ID of the member of staff.

Subtle typeface changes

Many images contain text, and subtle typeface changes are one easy way to create unique versions. For example, with a serif font, a version could be created with a single pixel missing from a single stroke of a single instance of a single letter. Font sizes can also be scaled up or down by as little as one pixel.

Non-subtle typeface changes

Sometimes, Apple uses the opposite approach, and chooses very unsubtle changes. If it wants employees to be very aware that their copy is unique, it has used things like random italics or bold. For example:

This year, the iPhone 15 will launch on Tuesday August 29 instead of the usual September timing.

This is an approach we’ve seen Apple take with documents sent to store staff ahead of product launches, in order to make it painfully clear that the company is watching. Even though an employee may retype something, rather than copying and pasting, it will make them fear other identifying features, such as …

Wording or punctuation changes

Tiny changes in wording are trickier if you’re trying to provide a unique copy to a lot of people, but can be very helpful once you’ve narrowed it down to a handful of people. For example:

This year, the iPhone 15 will launch on Tuesday August 29 instead of the usual September timing.

versus:

This year, the iPhone 15 will be launched on Tuesday August 29 instead of the usual September timing.

versus:

This year, the iPhone 15 will launch on Tuesday August 29, instead of the usual September timing.

The addition or removal of something as subtle as a comma can be enough.

Again, we will paraphrase to avoid this trap.

False information

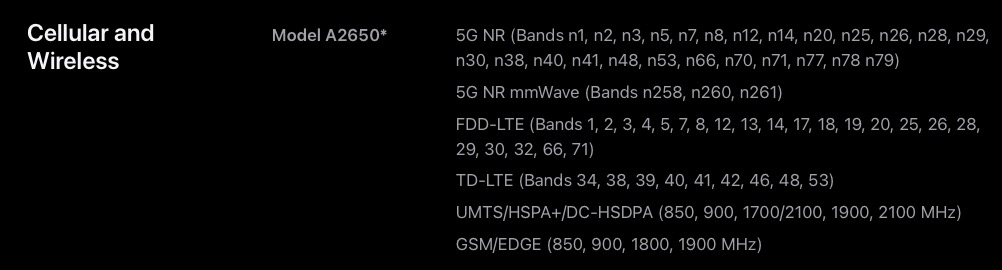

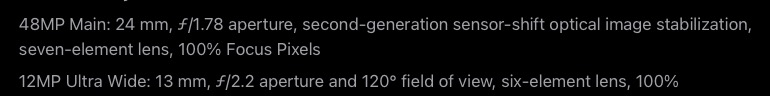

A simple approach with things like specifications is to have a tiny change of detail in each copy of the document. This would, obviously, need to be to an element the employee concerned isn’t working on.

For example, for an employee whose work does not relate to radio bands, imagine how easy it would be to change a single digit in this:

Or for one working on radio bands, changing f/1.78 to f/1.76 in this:

Fake dates, prices, colors, and more are possible.

In terms of how Apple catches leakers, these are just some of the ways we know or suspect the company uses.

Is @analyst941’s claim true?

It’s impossible to say. The closest we’re ever likely to come to knowing is seeing how many of their other claims are true – but even then, if it was indeed a multi-step narrowing-down process, we don’t know at what point Apple started feeding false information to the sister.

I said at the beginning that their claim is broadly consistent with tactics used by Apple. However, in this case the fake info was that Final Cut Pro was scheduled for a release on iPad in 2024, followed by Logic Pro in 2025 – when the reality is that both would be released just days later.

That’s a massive difference between real and fake info, when a much subtler difference would have achieved the same thing. Apple could, for example, have seeded the info that FCP would be released in June, and Logic Pro in July. It would have been much harder for an employee to know that a smaller difference was false.

So personally, while the tactic is a known one, I’m a little skeptical in this particular case.

Photos: Opt Lasers/Unsplash and Emiliano Vittoriosi/Unsplash

Add 9to5Mac to your Google News feed.

FTC: We use income earning auto affiliate links. More.