In the Atlantic Ocean, between the coasts of West Africa and the Caribbean, there’s a disjointed series of mats and clumps of brown, tangled algae known as sargassum seaweed. It’s supposed to be there. Or, at least, some of it is. In the Sargasso Sea—the only sea without a land border, bounded instead by four currents—sargassum offers critical habitat to marine life and is an integral part of the ecosystem.

What Was Your First Experience with Super Mario Bros? | io9 Interview

But in recent years, things have gotten off balance and out of hand, causing problems for people, the tourism industry, and wildlife. The size of the annual seaweed blob has been growing larger, likely because of climate change and increases in nutrient pollution brought on by human activity. Now, this year’s sargassum mass has officially reached record proportions.

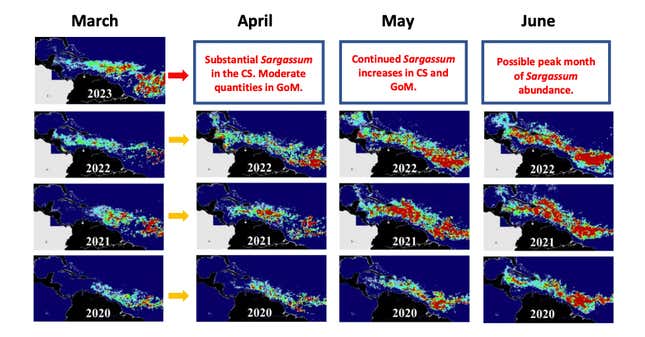

The discontinuous blob currently comprises an estimated 13 million tons of algae and spans about 5,000 miles of ocean from east to west, according to the University of South Florida’s Optical Oceanography Lab, which has been tracking these sargassum blooms for over a decade. It’s a “record abundance … for this time of year,” wrote USF researchers in a March 31 dispatch. And it’s expected to get even bigger before the warm months are through. Generally, the seaweed hits its peak in June and July.

With the newest data in hand, it’s near-certain that the sargassum is set to cause disruption and difficulties for the Caribbean islands and parts of Florida and Mexico, the scientists noted. The seaweed has already started to wash up across the region, and “major beaching events are inevitable around the Caribbean, along the ocean side of Florida Keys and east cost of Florida,” says the USF forecast.

G/O Media may get a commission

Why Is Sargassum a Problem?

When sargassum goes from the open ocean to the coastal ecosystem, it can muck things up, especially in mass quantity. Stranded and decomposing on beaches, it releases rotten egg-smelling hydrogen sulfide gas. On top of being odorous and unpleasant, this can cause potential respiratory irritation, digestive issues, and neurological problems for people nearby. It’s more than enough to ruin a beach day and obviously is a big problem for regional tourism—which depends upon inviting, un-seaweedy stretches of sand.

Resorts in Mexico, the Caribbean, and Florida alike all work to remove the algae when it arrives on their shores, either by employing workers to shovel it by hand or with machines. It can quickly become an expensive endeavor. Last year, Miami-Dade County spend $3.9 million on sargassum clean-up, an increase of more than $1.1 million from the year before, per the Miami Herald.

Aside from the tourism industry, the influx of seaweed can also obviously harm locals who live nearby the coast and/or rely on a coastal industry for their livelihoods. On top of the unpleasant health impacts of large quantities of beached sargassum, mats of the algae can strand boats and impact fishing.

For near-shore ecosystems, the seaweed mats can choke up shallows, blot out sunlight, and smother coral reefs. As the sargassum breaks down, it depletes oxygen in the water column and can degrade water quality, killing fish and other sea life.

What’s Causing the Seaweed Bloom?

The exact cause of this year’s bloom isn’t known. But research suggests it’s likely a result of compounding factors. Both nutrient pollution and climate change are thought to boost the severity of the sargassum’s seasonal proliferation. Things like agricultural runoff, sewage, storm events, upwellings, Saharan dust storms, and deforestation may force a flood of nutrients into the ocean that fuels rapid algal growth. Warmer waters, changes in marine overturn, and increasing rainstorms causing runoff from the Amazon basin—all influenced by climate change—are also thought to be factors.

Without some big changes in how humans are doing things, the annual influx of sargassum will likely continue to be a worsening problem. “We need to get back to the Goldilocks Zone,” Clarissa Anderson, executive director of the Southern California Coastal Ocean Observing System, told Inverse. “Just enough, but not too much.”